The follow-on from Bugatti’s Chiron was always going to be something special. Long the apex predator of the hypercar world, modern Bugatti has been defined by its industrially complex, quad-turbo W16 engine. When the brand passed into the stewardship of Mate Rimac, plenty assumed its next masterpiece would be all-electric. Rimac had other ideas: in early 2024 he confirmed that the next Bugatti would retain an ICE, and a 16-cylinder at that. That car turned out to be the Tourbillon, named after the watchmaking complication considered by many to be one of the pinnacles of the art. It was later revealed that those 16 cylinders would be arranged in a V, not a W, and the engine would be built by none other than Cosworth, which has become the go-to for those wanting automotive artistry in their hypercars’ engine bays. In the past five years it has built combustion powertrains for the Aston Martin Valkyrie, GMA T.50 and T.33 and, most recently, Adrian Newey’s magnum opus, the Red Bull RB17.

AESTHETIC APPEAL

The Bugatti project saw Cosworth involved in design-related matters to a greater extent than on previous engines it had developed» The story began for Cosworth long before the public even got a sniff of Rimac’s plans, with a call from a number that company MD, Bruce Wood, didn’t recognize. “Like most of us, I rarely answer, but maybe one in five times I will, in the hope that it is someone I really want to talk to.” In this case, it was worth answering: Mate Rimac was on the other end of the line. At the time (early 2021), “There was only so much he could say,” Wood recalls. “But he alluded to the fact that he was going to be part of a big, existing brand and wanted to do something very different. Of course we were going to be interested, and though at the time I had no idea it would be Bugatti, Mate had a huge reputation in the industry and I said, ‘Okay, let’s talk again next week’.” As those weeks progressed, the frankly astounding storyline of Mate – who began building electric cars in his garage at the age of 18 – taking over Bugatti alongside Porsche began to unfold.

The initial plan was to take the existing W16, remove the turbos and make it naturally aspirated, to create a hybrid with a 50:50 split between ICE and electric power. Wood acknowledges the excellent pedigree of the VW lineage of narrow angle V and, later, W layout engines. “Hats off to the VW Group,” he says. “Over the last 30 years they have managed to make that architecture into all sorts of things, but that doesn’t make it a nice, normally aspirated, high-revving architecture. So we said, ‘What about a V16?’” The die was cast for what may be Cosworth’s most spectacular creation since the 20,000rpm F1 CA V8.

LAYOUT CHOICES

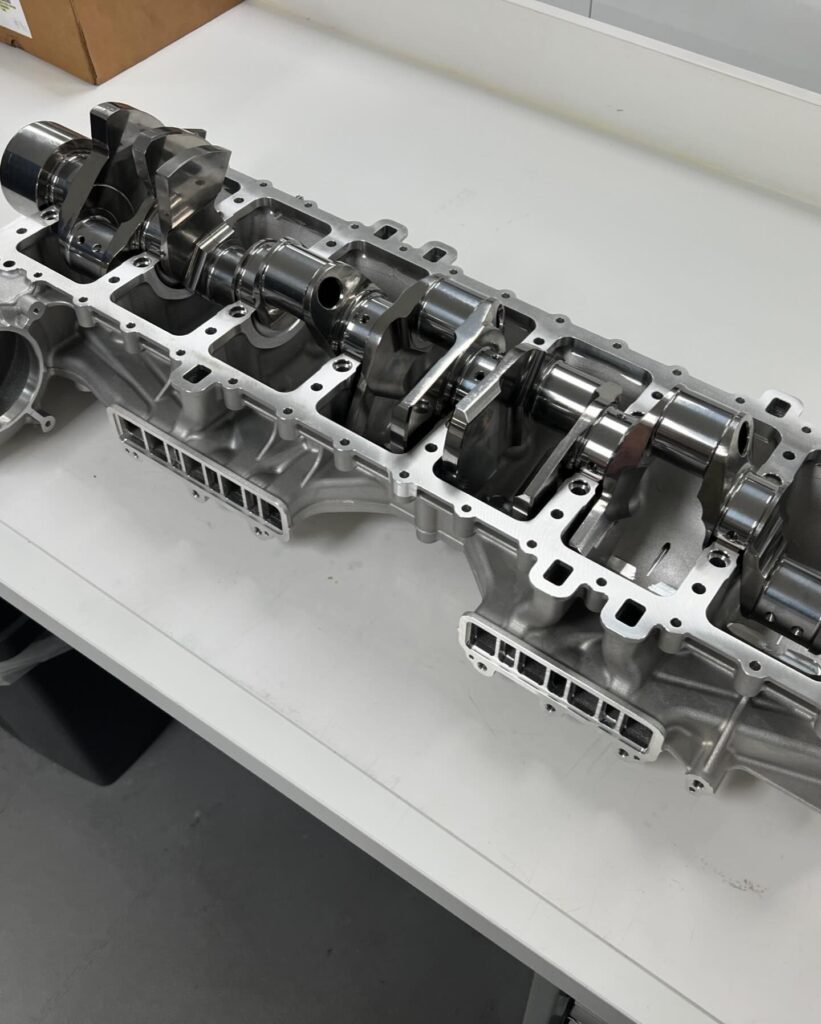

The basic specs of the engine Cosworth has developed for Bugatti are (relatively) conventional. A 92mm bore with a 78.55mm stroke gives a capacity of 8.3 liters, with a 90° bank angle, cross-plane crank and an all-up weight of 252kg. This last figure is particularly impressive as it is lighter than the 6.0-liter V12 Cosworth in the Valkyrie. It runs a dry-sump system and is bereft of ancillaries such as alternator and starter, with their roles handled by the hybrid. During the early concept stages of the project, a hot-vee design was toyed with. “In the first few weeks of talking with Mate, trying to win him over on the idea of a V16, we took two of our V8s in CAD and put them together, with some plenums and this amazing snake pit of exhausts in the center of the vee. That worked wonders, and I think that was the model that he presented to VW’s board,” says Wood. Ultimately, the overall vehicle package dictated that a more traditional cold vee be adopted.

These first stages of development were more involved than Cosworth was used to. With a 45% stake in Bugatti, Porsche had a voice and there were many more stakeholders involved in signing things off than there had been with the GMA projects. However, Wood is full of praise for Porsche, its cooperative approach and the way it allayed any initial fears about stepping on another equally storied manufacturer’s toes. Both weight and overall length were key constraints on the engine and here Cosworth’s know-how reaped benefits. For example, Wood notes that the use of a linerless block – Cosworth has in-house capabilities for bore coating – meant the distance between the cylinders could be closed up, keeping the overall length under 100cm (the crank is 900mm long). “The liners are around 12mm thick, so you save that on each cylinder,” he explains. “Not having the liners also saves weight, so the plasma-coated bores are important.”

The maximum RPM of the engine, set at 9,000 to best suit the character of the car, also enabled other areas to be optimized with weight in mind. For example, single rather than double-valve springs could be used, which may not seem like a big deal until you consider that there are 64 valves. Then there are the more obvious elements such as the titanium rods and extensive structural optimization of large components such as the block and heads. One might assume that having camshafts and crank nearly 1m long would create headaches with harmonics, but the more sedate rev ceiling (relative to the Valkyrie or T.50) helped. Whereas those engines feature a fully gear-driven cam train, the Bugatti runs chains.

“A chain has a lot of natural compliance, so you do not need the tuned stiffness elements in the gear drive,” explains Wood. The added bonus being a chain drive system is lighter than an equivalent gear setup. “A chain has a lot of natural compliance, so you do not need the tuned stiffness elements in the gear drive” One unforeseen circumstance nearly tripped up the team. “One of the drivers when we started this was thinking, ‘how big are our machines, can we fit this in?’” says Wood. “Luckily, we didn’t need to change anything but we are on the ragged edge of our machine capacity with about 5mm to spare on the block and heads.”

EMISSIONS AND INTEGRATION

“Everyone knew that the really hard bit was going to be making the 1,000bhp engine talk to the 1,000bhp electronics,” says Wood. This required close cooperation between the teams at Cosworth, Bosch (which has handled the electronics), Dana (transmission) and, of course, Bugatti. “Bosch provides the engine management and calibrated the engine, so they were front and center to the collaboration between the engine and electric motors,” Wood reports. “When it first ran, we all assumed it would take months to get ready for real vehicle testing, but within a week the car was running robustly at Bugatti’s test track in Croatia, and within about three weeks they were down at Nardò. I would say one of the big achievements was getting the engine and motors talking to each other, via the gearbox, and running so convincingly. It’s been a great piece of collaboration.”

Cosworth had gained considerable experience in achieving emissions compliance from high-revving, naturally aspirated engines with its recent projects, so the V16 builds on that. Ensuring legality involved extensive work on the combustion system and also the interactions with the electric powertrain. However, Wood points out, “The electrification helps significantly, but the way the regulations have developed means you cannot just rely on running electrically. The regulations have caught up and it doesn’t give quite the same advantage as before.”

Cosworth kicked off the Bugatti project with a mule engine. “Previously, that was an in-line three-cylinder and now it’s an in-line four,” says Wood. “We followed that same methodology and hence were able to develop the combustion system and emissions way before we fired up the 16.” Impressively, the V16 is a cleaner-running engine than either of the V12s.

Concurrent with behind-the-scenes work to ensure regulation compliance, Cosworth was also on a learning curve when it came to the commercial aspects of the engine. Wood notes, “You might think Bugatti, the most expensive car maker in the world, wouldn’t worry about the cost of the engine, but believe me they do. It has to be built to a price, even if that is an expensive one! That was a big challenge – simply because there are so many parts to it – and a big element of the production planning process. It has been a great learning experience for us.”

Cosworth also had to handle inpuits from the vehicle styling team in a much more involved way than on previous projects. For example, nearly 30 iterations of the plenums (which are on full display at the rear of the Tourbillon) were run through before a final design was settled on. “Frank Kyle, the designer of the car, made a really good point from the beginning,” recounts Wood. “We have 16 cylinders; small kids need to be able to say, ‘Dad, Dad, look, there are 16 cylinders.’ There needed to be some feature that you could count to 16, to make sure everyone knows.” It is impressive that such a complex engine as the V16 can be brought to fruition in not much more than three years, and this is testament to Cosworth’s expertise and motorsport ethos. Wood comments, “All projects inevitably have bits that become a greater issue than expected, but this one, so far, has gone extremely smoothly. We’re very, very pleased with how the project has come out.”

The Tourbillon marks the start of what will likely be Cosworth’s largest production run – 250 units – and will inevitably spawn new models along the way. The bellowing V16 is here to stay: “We will certainly be seeing the V16 for many years to come,” asserts Wood.