APTI visits GM’s Global Technical Center in Michigan to get to know the company’s new Ultium battery tech and how it plans to use it.

General Motors has been producing electrified vehicles for several years, but its new Ultium architecture introduces the OEM’s third-generation BEV3 batteries and a more scalable solution. APTI discusses the new platform with Tim Grewe, GM’s director of electrification strategy and cell engineering.

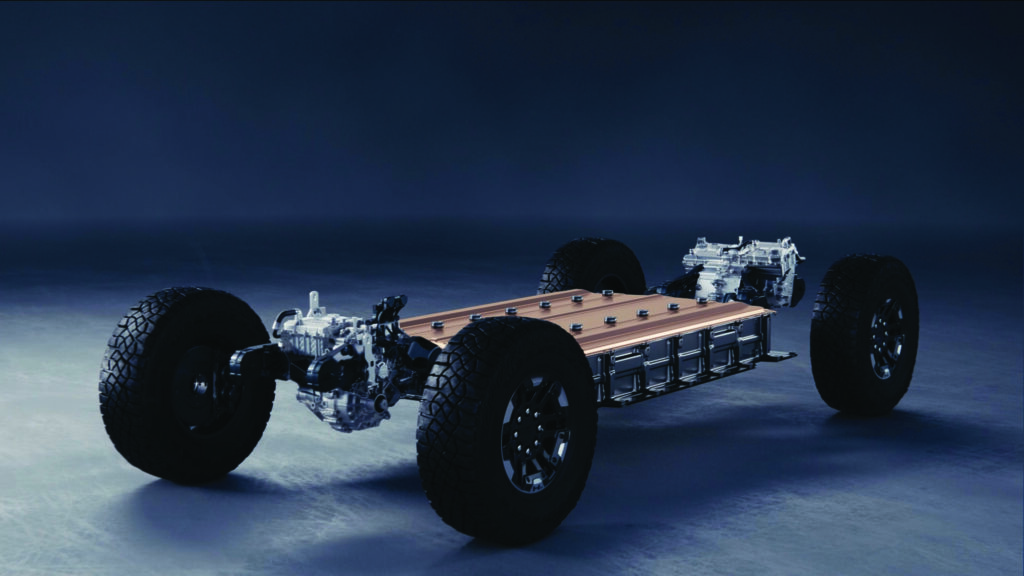

Ultium has been optimized for crossovers and SUVs but can also be used in pickup trucks and is future-ready to be used in autonomous vehicles as GM heads toward its stated corporate goals of zero crashes, zero emissions and zero congestion.

The building blocks of Ultium are the battery cells, developed jointly by GM and LG. They are large-format pouch cells, 580mm long and 115mm tall, dimensions defined by manufacturing capability optimization. They run across the width of a vehicle and can be fitted into anything from a Cadillac Lyriq to a Chevrolet Blazer or the Hummer EV. The cells can also be placed horizontally 60mm or 80mm apart, which enables them to be placed under the rear passenger footwell in a performance sedan.

Taking the Lyriq as an example, Grewe says there are 288 cells under the floor providing 104kWh of usable energy under the EPA test cycle. High-energy-density electrodes provide around 620Wh per liter at a cell level. The key differentiator, says Grewe, is the cathode chemistry: “Some people use a nickel cobalt aluminum chemistry, some use a nickel cobalt manganese; we use nickel cobalt manganese and aluminum.

“With that, we get very good cycle life. At high temperature we hold cycle life better, the cathode does not degrade as much. Resistance to micro cracking and having to reform barriers inside the cell is the best and so if you look at our Bolt 2016 it was cobalt manganese. We took the cobalt down by 70% because of the high-cost nature of it and the environmental, social and governance issues with cobalt. We reduced the cost by 40% compared with the Bolt EV.”

However, Grewe won’t divulge the exact make-up of the materials, acknowledging that this is a very competitive area of the auto industry where everyone likes to keep things secret. But he is more than happy to discuss the anode and cathode engineering.

Anode innovation

The anode is made from artificial graphite carbon, which is common across the industry. However, Grewe says that because it takes six carbon elements to hold one lithium ion, future development will see the mixing of carbon with silicon, as one element of silicon can hold one lithium ion. Yet, because silicon expands more than graphite, Grewe says the team decided to use a uniform electrode rather than a wound one in order for Ultium to be future-ready for a change in the composition.

“Today a wound electrode works, it’s in the industry, but for future expanding technology – silicon, lithium metal technology – which expands a lot more, we’re investing now in the uniform electrodes to be able to take that expansion while maintaining life. That was one of our fundamental strategies,” Grewe explains.

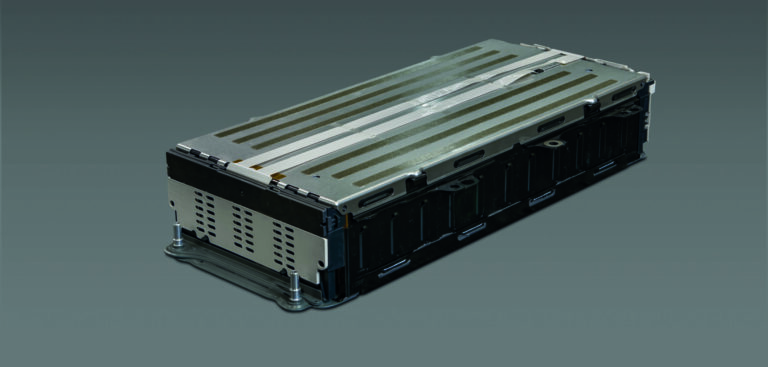

The cells themselves are grouped in a cell module assembly (CMA) in batches of 24 to create a serviceable unit, with each module providing around 9kWh. The bulk of the pack assembly is done by robots that stack the cells, form the leads, weld them together and insert them. Welded connections require less space and provide lower resistance and thus reduced heat rejection, according to Grewe. This is not common practice though, with most top terminal cells being bolted in, although he expects that most companies will switch to welding once they get to full volume production and they have the requisite welding technology.

Photo by John F. Martin.

Service considerations

The packs are engineered to be serviceable at a GM dealership level, where the lid can be removed and a CMA replaced if necessary. Each has its own QR code so material content and history can be checked. This also helps for future recycling needs.

Photo by Steve Fecht for General Motors.

The packs also incorporate the necessary monitoring and balancing electronics, as well as the thermal management components, all of which communicate wirelessly with the vehicle.

This creates a mesh network in the vehicle that reduces wiring by around 90%, which GM sees as a big advantage in reducing potential failure points. It also assists with over-the-air updates and moving more of the vehicle computing away from the vehicle itself and into the cloud.

“We’re no longer limited to the on-vehicle computing capability and knowledge; we also put it up into the cloud and we add that into the Ultium,” explains Grewe. “With that we really think that we can meet all of our customers’ needs with a lot less proliferation, and we can be much more agile as the customers change their preferences into new technology. We think Ultium is a very good solution now, but we do plan to upgrade it for the future and [thanks to the] architecture we are going to be able to do those upgrades with minimal disruption in a continuous fashion.”

The battery packs themselves can also be scaled. There is a single 12-module pack on the Lyriq, while on the Hummer EV one pack is placed on top of another. It’s also possible to switch to a pack containing 10, 8 or 6 modules for smaller models, but Grewe says these would be future products that are not currently planned – or rather, cannot be discussed.

“When we did Ultium we wanted to span the light commercial vehicles and heavy-duty vehicles all the way down to a small SUV, and our optimization just worked out there,” says Grewe.

“There are other OEMs that have a very similar structure with this, where they have a cell module assembly and a little less energy, and they generally don’t go as far as we go up in terms of size of vehicle and energy storage,” he continues. “Ultium is one architecture across all of that. The closest competitor has two architectures and manages that with two different submodules and assemblies. Many OEMs have three or four architectures. We think that this was an optimization around our portfolio and our needs.”

There’s a lot of commonality in some of the components and chemistry composition today, but Grewe says GM is running continuous design loops looking at alternatives that could take the energy from the existing 620Wh per liter to 850Wh, even 1,100Wh with lithium metal anodes. This could reduce the pack size and therefore the mass in a vehicle, all of which are scenarios being looked at as the technology evolves.

Recycle and reuse

GM is investing in raw material ventures while also looking to a future where it is less reliant on mining and more reliant on recycling.Every OEM is conscious of the need to have a secure and sustainable flow of raw materials to meet electrification needs. This is also true for GM, which has supply agreements in place until 2025.

“Our goal for a secure value chain is to get 120% of our needs secured well ahead of our expansion,” says Grewe. Currently most of GM’s lithium supply comes from Australia but it is looking to localize to reduce costs while also seeking out better technology.

GM has invested in a company called Controlled Thermal Resources, which undertakes direct lithium extraction from lithium brine in the San Andreas Fault in California. GM is also collaborating on a cathode active material factory with Pasco Chemical Company in Canada, which uses low-cost hydro energy. Ultimately, Grewe hopes to reach a point where there is less reliance on new raw materials.

“We recycle every battery we get and we provide our customers with a recycling pass, although it’s only a recommendation as technically we don’t own those batteries,” he says.

Photo by Santa Fabio for General Motors.

Test runs

GM’s Estes Lab at its Global Technical Center in Michigan is responsible for development and testing of battery cells.GM has joint ventures with LG Energy Solutions in Lordstown, Ohio, and Spring Hill, Tennessee, to manufacture battery cells, but its development and testing takes place in the Estes Lab at the Global Technical Center in Michigan.

APTI took a tour of the facility with Eric Boor, senior leader at GM. There, batteries, including the latest BEV3 Ultium, are run through test cycles for anything from one hour to three years. The test rigs can push up to 500A into each cell, which Boor says is the maximum current they are willing to use from a safety perspective.

The facility can test individual cells, cell module assemblies and full packs, and even multiple packs in the case of tests for the Hummer EV. Each cell can be subjected to a multitude of operating conditions at once, including power and temperature variations, with equipment to test between -68°C and +89°C and 5-95% relative humidity.

The star of the facility is a large, climate-controlled shaker rig, similar in size to those used by Boeing to test airframes.

“We can vibrate from zero to 2,000Hz, which will simulate any road condition our customers are going to go through,” says Boor. “The drum will rotate in three axes, so we can give x-axis, y-axis and z-axis shapes to simulate a battery in all the different corresponding environments that it is going to go through.”

The lab can also simulate a range of temperature and humidity conditions, but more than that, can push up to 1,500kW of energy into a battery pack at 1,500A, which is essential for testing the Hummer EV battery pack, in particular the so-called Watts to Freedom launch control feature, which can draw out 1MW in as little as three seconds.