Research at WMG at the University of Warwick has enabled the development of a new direct, precise test of lithium-ion batteries’ internal temperatures and electrode potential. This means that the batteries can be safely charged up to five times faster than the current recommended charging limits.

The new technology works in-situ during a battery’s normal operation without impeding its performance and it has been tested on standard commercially available batteries. The new technology will enable advances in battery materials science, flexible battery charging rates, and thermal and electrical engineering of new battery materials/technology, and it has the potential to help the design of energy storage systems for high-performance applications such as motor racing and grid balancing.

If a battery becomes over heated it risks electrolyte damage and can lead to electrolyte break down, forming gases that are flammable as well as causing significant pressure build up. Overcharging of the anode can lead to so much lithium electroplating that it forms metallic dendrites and eventually pierces the separator causing an internal short circuit with the cathode and subsequent failure.

To avoid this, manufacturers stipulate a maximum charging rate or intensity for batteries based on what they think are the crucial temperature and potential levels to avoid. However, until now internal temperature testing (and gaining data on each electrode’s potential) in a battery has proved either impossible or impractical without significantly affecting the battery’s performance.

However, researchers in WMG at the University of Warwick are developing a new range of methods that allows direct, highly precise internal temperature and per-electrode status monitoring of lithium-ion batteries.

Tested on commercially available automotive-class batteries, the data acquired using the WMG’s methods is much more precise than external sensing and WMG has been able to ascertain that commercially available lithium batteries could be charged at least five times faster than the current recommended maximum rates of charge.

“This could bring huge benefits to areas such as motor racing which would gain obvious benefits from being able to push the performance limits, but it also creates massive opportunities for consumers and energy storage providers,” said Dr Tazdin Amietszajew, researcher at the WMG.

“Faster charging as always comes at the expense of overall battery life but many consumers would welcome the ability to charge a vehicle battery quickly when short journey times are required and then to switch to standard charge periods at other times. Having that flexibility in charging strategies might even help consumers benefit from financial incentives from power companies seeking to balance grid supplies using vehicles connected to the grid.

“This technology is ready to apply now to commercial batteries but we would need to ensure that battery management systems on vehicles, and that the infrastructure being put in for EVs, are able to accommodate variable charging rates.”

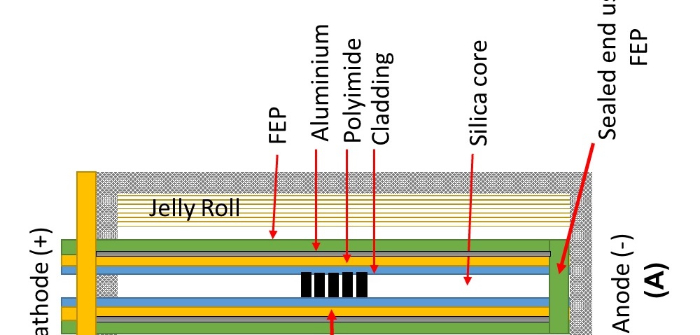

The technology the WMG researchers have developed for this new direct in-situ battery sensing employs miniature reference electrodes and fiber Bragg gratings (FBG) threaded through bespoke strain protection layer.

An outer skin of fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) was applied over the fiber, adding chemical protection from the corrosive electrolyte. The result is a device that can have direct contact with all the key parts of the battery and withstand electrical, chemical and mechanical stress inflicted during the batteries operation while still enabling precise temperature and potential readings.

“This method gave us a novel instrumentation design for use on commercial 18650 cells that minimizes the adverse and previously unavoidable alterations to the cell geometry,” added WMG associate professor Dr Rohit Bhagat. “The device included an in-situ reference electrode coupled with an optical fiber temperature sensor. We are confident that similar techniques can also be developed for use in pouch cells.”

“Our research group in WMG has been working on a number of technological solutions to this problem and this is just the first that we have brought to publication. We hope to publish our work on other innovative approaches to this challenge within the next year.”