The Technical University of Munich (TUM), in collaboration with Forschungszentrum Jülich, has developed an all-new battery testing process designed to directly investigate lithium anode deposits, which build-up when a lithium-ion battery is charged too quickly, resulting in reduced battery capacity and life.

The deposit of metallic lithium on the anodes of lithium-ion batteries is one of the primary factors that limits charging current. The performance of batteries suffers significantly from the metallic deposit. When charging batteries, the positively charged lithium ions move through the liquid electrolytes and are deposited in the porous graphite anodes.

However, the larger the current and the lower the temperature, the greater the probability that the lithium ions will not be deposited within the electrodes, as desired, but rather as a solid metallic layer on the outer surface.

“Using traditional methods of microscopy, we can only observe a battery after use, because it needs to be opened,” said Dr Josef Granwehr at the Jülich Institute of Energy and Climate Research. “During this process, further reactions that distort the results become inevitable.”

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy, however, can be readily integrated into laboratory procedures. The method is akin to the better-known nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, but focuses on electron spins rather than atomic nuclei.

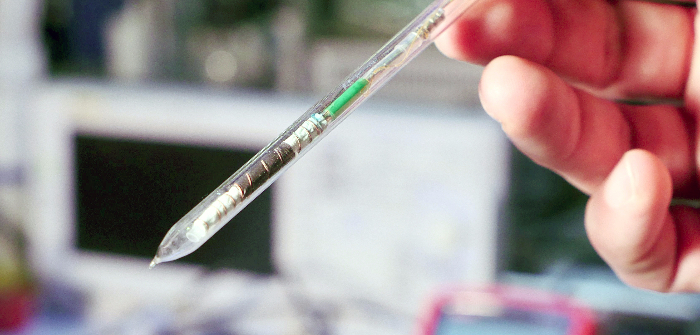

“The key to detecting lithium plating using EPR was the construction of a test cell compatible with the requirements of EPR spectroscopy while exhibiting good electrochemical properties,” said Dr Johannes Wandt. “The geometry is also important. Precise measurement results are contingent on the sample being exposed to the magnetic field but not the inevitably present electric field.”

“Using this process, it is now for the first time possible to investigate lithium plating and the associated processes in a differentiated manner that is relevant to a whole array of applications,” added Rüdiger Eichel, director at Jülich Institute of Energy and Climate Research. “Our testing process makes determining the maximum charging current before lithium plating sets possible, as well as ascertaining other boundary conditions such as temperature and the influence of electrode geometry.”