According to a report recently published by manufacturing consultancy HSSMI, the UK must rapidly accelerate the establishment of gigafactories and new battery technology development or risk losing domestic car production altogether.

“Electrification is increasing demand for the battery cells and packs powering electric vehicles,” said Axel Bindel, executive director of HSSMI. “The UK in particular is at a pivotal moment. By 2040, there will be a need for 140GWh in battery cell capacity, equivalent to five gigafactories. Currently, however, there is only 3GWh of production in the UK and, by 2030, just a further 45GWh planned, leaving a major gap – over 95GWh – between the rate of battery plant establishment and planning and the forecast demand. That is where HSSMI can play a crucial role.”

HSSMI advises global OEMs and Tier 1 suppliers on the design of manufacturing plants, optimization of production efficiency and introduction of circular economy principles. It notes that thanks to the accessibility of abundant natural resources, as well as government-driven support for high-volume manufacturing and local demand for electric vehicles, the majority of global battery production – roughly 70% – is currently in Asia.

The UK, on the other hand, faces challenges including a lack of skilled technicians for cell manufacturing processes and availability of critical raw materials, as well as high production costs. Investing in more battery plants and bringing them as close as possible to car production – reducing supply chain challenges – can alleviate many of these issues, but the industry needs to act quickly. It is clear that the government is starting to make funds available for the industry, with more collaboration potentially needed to steer the country to success.

Robin Foster, battery solutions lead at HSSMI, explained. “Typically, it could take a gigafactory up to five years from an initial idea to become fully operational. Demand for cell manufacturing, however, is expected to surge in the next four to five years. It is not enough to have one or the other – we can’t focus just on gigafactory creation without being strategic about new technologies. So in parallel, the UK must exploit and commercialize the wealth of new battery technology developed locally. The typical time, however, for new technology to become commercially ready can be 10 years from lab to high-volume production. Engagement with a scale-up specialist can provide feedback early on for commercial viability, disrupting the traditional linear development program and speeding up the time to market.”

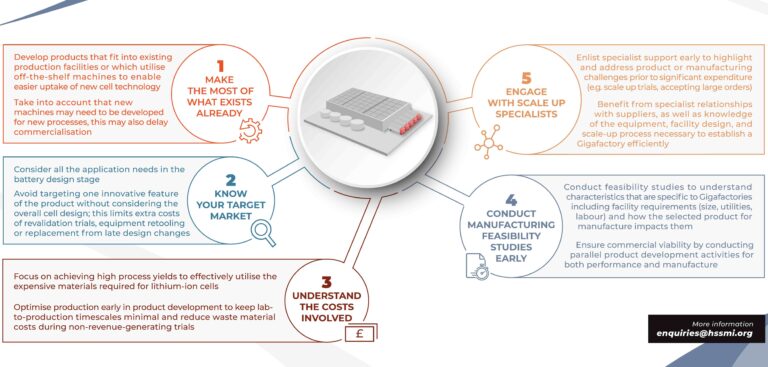

HSSMI has laid out five key steps in its report, which it claims will allow the UK to accelerate gigafactory creation:

Make the most of what exists already

Developing products that can fit into existing production facilities or use off-the-shelf machines will enable easier uptake of new cell technology. Where new processes are created, a further development program will be required for the manufacturing machines, potentially delaying commercialization.

Know your target market

The design of a new battery must be focused on all the needs of the application. While development may target one parameter, such as high-capacity chemistry, application requirements for other aspects (cell size, electrode specification) can lead to late design changes, extra costs through revalidation trials, equipment retooling or replacement.

Understand the costs involved

Materials used in lithium-ion cells are expensive, so high process yields are critical. Taking steps toward optimized production early in product development is key to keeping lab-to-production timescales minimal and reducing waste material costs during upscaling activities.

Conduct manufacturing feasibility studies early

Feasibility studies are important to understand gigafactory-specific characteristics, facility requirements (size, utilities, labor) and how the product selected for manufacture influences them. Unique cell design features that increase production time or complexity could lead to unprofitable products. Early studies facilitate parallel development of the product for performance and manufacture to ensure commercial viability.

Engage with scale-up specialists

Specialists can address many challenges swiftly, saving time and money through leveraging existing supplier relationships, equipment knowledge, facility design and scale-up experience.

Trends are already emerging of automotive OEMs partnering with cell manufacturers and entering into joint ventures to secure battery cell supply. Staying close to cell manufacturers allows automotive OEMs to eliminate supply chain risks such as concerns about transporting dangerous goods and longevity of supply, and use the opportunity to co-develop battery cells, packs and EVs. HSSMI believes the UK must attract and develop high-volume cell manufacturing capability to decrease the temptation for domestic automotive OEMs to seek opportunities elsewhere.

“At the moment, the Envision AESC facility in Sunderland is the only UK facility manufacturing lithium-ion cells at scale (2-3GWh). AMTE Power and Britishvolt have both announced plans for UK-based gigafactories that will help supply local products to the UK automotive sector,” added David Stewart, engineering director, research and innovation at HSSMI. “Nonetheless, further investment in the UK automotive industry is crucial, as it has been plummeting since 2013 and in 2018 inward investment amounted to only £0.59bn [US$0.83bn].

“Government-backed bodies such as the Advanced Propulsion Centre and the Faraday Institution are continuously working to accelerate battery technology by promoting and catalyzing innovation and collaboration between manufacturers, technology providers, automotive OEMs, research organizations and academics, through various funding opportunities.”

HSSMI believes it is critical that the government continues to back the work of these organizations and that R&D funding is channeled into the automotive industry.

“Action to ramp up capacity needs to be taken within the coming year,” concluded Bindel. “In the most detrimental scenario, UK-based automotive OEMs would seek to leave the country. This would adversely affect the entire economy, not just the automotive sector, as it accounts for 14.4% (worth £44bn [US$62bn]) of total UK exports of goods. But with close collaboration between investors, customers, government, technology developers and suppliers, the challenges can be overcome to provide competitively priced, high-quality, high-performance, even potentially world-leading, battery cells.”