I recently debated with a friend about what will be the main source of vehicle propulsion in 2030. He is convinced that internal combustion will have had its day in 12 years’ time, it being the niche choice for specialist vehicles only. Battery electrics, he says, will be the mainstay in 2030. This comes on the back of the UK government boldly stating that only electrically powered cars may be sold on its soil from 2040 onwards. However, sadly for my visionary friend – and the UK government – there’s no business logic to the outright death of the ICE for volume cars – not in the timescales they envisage anyway.

Right now, in your R&D lab and on your dynos, you, the engine designers that read this magazine, are currently working on brand-new internal combustion engine designs. I know this to be fact because we speak to our readers and we listen.

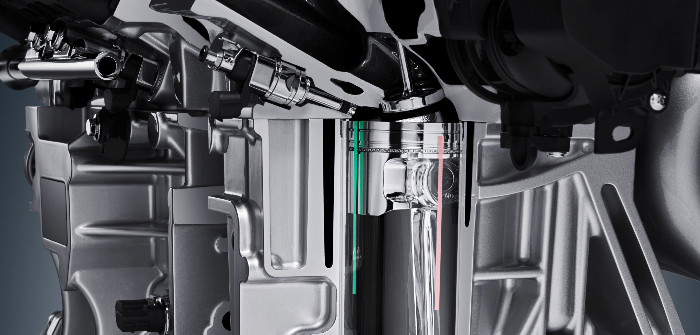

Let’s look at the timescale. The CAD drawings start today for a new engine that will power your volume sellers. It’s a brand-new, spark-ignition design, with next to no carryover parts. Let’s say you speed engine development in record time. I gather 36 months would be pretty rapid in this day and age for a clean sheet of paper design. That takes us to launch in May-June 2021. But hang on, we need a car to put it in. Sorry, no, we need cars – plural – because all but gone are the days in which there was one engine design per model. (Try to think of how many bespoke engines are currently in mass production. Ford’s Focus RS engine, perhaps? Even that unit is heavily based on the item used in the Mustang. I actually can’t think of one engine that’s unique to one mass-production model, with Ferrari also now well and truly on the one-size-fits-all bandwagon.) And so it’s May 2021, and we have our new engine and our new car to put it in, with more vehicles scheduled for market over the next 12 to 36 months that will use this new engine because economies of scale demand it. It’s now mid-2024 and you’ve only just launched a car with this 2021-released IC unit that you started developing in May 2018. Let’s give that car a minimum shelf-life of, say, six or seven years? Oh, it’s the year 2030-31 and a little fire still rages under the hood of one very popular, mass-production vehicle!

But there’s more, because if ICEs are to stop being sold by 2040 as the UK government demands, that means stopping all new engine R&D by 2025. That’s just seven years away, or to put it another way, the average market lifespan of any mass-production vehicle! Why stop all IC work by 2025? Go back through that timescale: launch an engine in 2025, and you’ll still be selling the car propelled by it in 2037/2038 for it to have made any economical sense to have developed it in the first place. Work on IC engines beyond 2025, and you’ll simply be producing an engine that won’t live long enough to

be financially viable.

And so according to my friend and the UK government, you’d better stop what you are doing right now! Sell your dynos and forget further improving fuel economy, lowering emissions, all that sort of stuff, for the next decade or so until all these BEVs somehow take over. You know, those vehicles that see range halved in cold conditions (or in the case of my Mini PHEV in the cold the other day, refuse to work altogether until the IC engine had warmed it enough to perform).

No, the future of the ICE is safe for the foreseeable, and the irony is, it’s batteries that will help that be the case – I predict plug-ins will dominate vehicle sales by 2030 and indeed in 2040. Logic, the rate of technology advancement, and economies of scale make that statement fact.

Graham Johnson